IN PRINT CONVERSATION ︎︎︎ Lawrence Brose and Lawrence Chua

In Cruising Utopia, José Esteban Muñoz calls attention to a passage in John Giorno’s book of poetry and memoir, You Got To Burn To Shine, where the artist enters a public bathroom in the Prince Street subway station. It is a space “rife with anonymous public sex” in which he encounters a young man with wire-rimmed glasses, a “kid” with “unusual passion.” The “kid” turns about to be a young Keith Haring, and the two have passionate hedonistic sex. When Giorno re-enters the subway, he finds himself stranded in a world of heteronormativity. He writes, “It always was a shock entering the straight world of a car full of grim people sitting dumbly with suffering on their faces and in their bodies, and their minds in their prisons.” Muñoz understands Giorno’s actions as an act of queer futurity. In the midst of the AIDS pandemic, the image of Giorno’s encounter not only conjured another time, but also formed a critique of the present and its limits. The images in Lawrence Brose’s films function in a similar way: they are at once a form of queer world-making and a reminder of the ways such images challenge the hegemony of the present. Splicing together food and shot footage that he has processed by hand and other alternative methods, Brose creates formally lush and critical films that open up new ways of thinking about how human beings have historically carved out or “queered” transgressive spaces in the midst of otherwise grim realities.

Brose himself is no stranger to either building critical spaces for creative practice or persevering in the face of repression Based in Buffalo, New York, Brose was a co-founder and Executive Director of the Center for Exploratory and Perceptual Art (CEPA), a community darkroom and exhibition space founded during the Alternative Space Movement in 1974. CEPA continues to pioneer critical photography and the photo-related and electronic arts, through exhibitions education, facilities, and an artist-in-residence program that serves working artists, urban youth, and other individuals. CEPA is a testament to the way that artist-run spaces can struggle, survive, and flourish outside of ‘Art World’ metropoles.

It has been nearly twenty years since Lawrence Brose made a film called De Profundis, which uses the letter written by Oscar Wilde while imprisoned in Reading Gaol to his lover to launch a lyrical investigation into queer longing and liberation.

Brose himself is no stranger to either building critical spaces for creative practice or persevering in the face of repression Based in Buffalo, New York, Brose was a co-founder and Executive Director of the Center for Exploratory and Perceptual Art (CEPA), a community darkroom and exhibition space founded during the Alternative Space Movement in 1974. CEPA continues to pioneer critical photography and the photo-related and electronic arts, through exhibitions education, facilities, and an artist-in-residence program that serves working artists, urban youth, and other individuals. CEPA is a testament to the way that artist-run spaces can struggle, survive, and flourish outside of ‘Art World’ metropoles.

It has been nearly twenty years since Lawrence Brose made a film called De Profundis, which uses the letter written by Oscar Wilde while imprisoned in Reading Gaol to his lover to launch a lyrical investigation into queer longing and liberation.

The 65-minute film is a milestone in experimental cinema, bringing together early 20th Century queer home movies, pornography, radical faerie confreres, and drag queen performances with poignant readings of Wilde’s letter. Throughout the film, Brose manipulates the colors, scales, and ratios of the footage to produce a film that seduces viewers even as it reminds them of the ways queer people have historically intervened on the narratives that structure heteronormativity.

The critical aspects of De Profundis did not go unnoticed. Nearly ten years ago, Brose was arrested by agents of the Department of Homeland Security’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement division and charged with possession of what the federal government claimed was “child pornography.” The agents seized a shared computer that was in Brose’s former loft, and which was used by the artist-in-residence program at CEPA. Although it was never proven that the computer—which could have been used by anybody who was staying in the loft—belonged to Brose, charges were brought against him for the possessing “1300 images” of child pornography, some of which were downloaded from a website in Germany, where images illegal in the United States may be legal. Although the original indictment was tossed out by a federal judge who found the evidence wanting, Brose was re-indicted by an ambitious federal prosecutor. After a five-year battle which took a huge toll financially and emotionally on the artist, Brose pleaded guilty to the lesser charge of obscenity and was put on probation for two years at the end of 2014.

In 2015, Brose exhibited print work for the first time since the case at the Body of Trade and Commerce gallery (BT&C) in Buffalo. The show, Indicted, featured work related to the images that were indicted in Brose’s legal case, the majority of which came from De Profundis. A new series of prints in the show, Incarcere et Vinculus (in prison and in chains), focused on a section of the film that related directly to physical imprisonment.

This interview took place in Brose’s former loft space in downtown Buffalo, where I have stayed when visiting the city. Although Brose long ago donated his former home to CEPA to host visiting artists and scholars, the place still maintains the ambiance of a space that has incubated transgressive work that the edge of the American Rustbelt.

The critical aspects of De Profundis did not go unnoticed. Nearly ten years ago, Brose was arrested by agents of the Department of Homeland Security’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement division and charged with possession of what the federal government claimed was “child pornography.” The agents seized a shared computer that was in Brose’s former loft, and which was used by the artist-in-residence program at CEPA. Although it was never proven that the computer—which could have been used by anybody who was staying in the loft—belonged to Brose, charges were brought against him for the possessing “1300 images” of child pornography, some of which were downloaded from a website in Germany, where images illegal in the United States may be legal. Although the original indictment was tossed out by a federal judge who found the evidence wanting, Brose was re-indicted by an ambitious federal prosecutor. After a five-year battle which took a huge toll financially and emotionally on the artist, Brose pleaded guilty to the lesser charge of obscenity and was put on probation for two years at the end of 2014.

In 2015, Brose exhibited print work for the first time since the case at the Body of Trade and Commerce gallery (BT&C) in Buffalo. The show, Indicted, featured work related to the images that were indicted in Brose’s legal case, the majority of which came from De Profundis. A new series of prints in the show, Incarcere et Vinculus (in prison and in chains), focused on a section of the film that related directly to physical imprisonment.

This interview took place in Brose’s former loft space in downtown Buffalo, where I have stayed when visiting the city. Although Brose long ago donated his former home to CEPA to host visiting artists and scholars, the place still maintains the ambiance of a space that has incubated transgressive work that the edge of the American Rustbelt.

Lawrence Chua: As an artist who works across disciplines, making a film like De Proundis that was based on a piece of music that was in turn made for a film that didn’t exist, or optically printing and using found images and then translating them into another medium, you must be attentive to what is gained or lost in the process of translation. I am often struck with how translating a text from, say, Thai into English, reveals much more about the text than might be ordinarily available by simply reading it in its original language. With De Profundis you began with Oscar Wilde’s letter, but rather than simply use it as the narrative for the film, you did something quite different. What were your intentions when you began working on De Profundis and how did that change over time?

Lawrence Brose: It began with Frederick Rzewski, an American composer who wanted to create a score for me and he was very interested in setting excerpts of Oscar Wilde's prison letter to music for a vocalizing pianist. We were trying to raise money to commission him and everything. Finally, he just said fuck it, I'm just going to do it for you. He went ahead and recorded it. I had a pristine recording of it, I had the score, everything. But, what happened was, I read all of the biographies, I did a lot of research and I was very frustrated because this letter, was often kind of seen as an example of Oscar Wilde’s mature writing. I realized that, NO, this is imprisoned language. There is a romantic existentialism in this letter that was further enhanced by the musical setting of it. I immediately went into resistance mode. I had to counter this.

LC: Counter what?

LB: The romantic existentialism of the letter. I wanted to explore and expose his transgressive aesthetics. The best way to do that was to mine his aphorisms, which really build on that way in which he used language to queer an idea. It takes you down one path and then goes the other way: "when you are alone with him, does he take off his face to reveal his mask?" Which is the opposite...most people would think does he take off his mask to reveal his true self. I was very frustrated because I couldn't find any critical analysis of Oscar Wilde's aesthetics and writings at the time. Finally Jonathan Dollimore's book came out, Sexual Dissidence: Augustine to Wilde, Freud to Foucault and that really was the piece that opened it up to me. By it's very nature the projects, especially my Film for Music for Film series is about translation to begin with. Another form of translation happened when I was grappling with the question of how to represent the dandy one hundred years later. There is a certain embodiment of that in Agnes de Garron, the founder of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, in the film, but I decided to embed the dandy in the emulsion of the film. That's where Wilde scholars always get frustrated with me when they come to see De Profundis. They are like where's Wilde? He's embedded in every frame of the film, he's infecting it.

LC: Why was this aspect of Wilde’s persona worth carrying forward? What made his dandyism transgressive?

Lawrence Brose: It began with Frederick Rzewski, an American composer who wanted to create a score for me and he was very interested in setting excerpts of Oscar Wilde's prison letter to music for a vocalizing pianist. We were trying to raise money to commission him and everything. Finally, he just said fuck it, I'm just going to do it for you. He went ahead and recorded it. I had a pristine recording of it, I had the score, everything. But, what happened was, I read all of the biographies, I did a lot of research and I was very frustrated because this letter, was often kind of seen as an example of Oscar Wilde’s mature writing. I realized that, NO, this is imprisoned language. There is a romantic existentialism in this letter that was further enhanced by the musical setting of it. I immediately went into resistance mode. I had to counter this.

LC: Counter what?

LB: The romantic existentialism of the letter. I wanted to explore and expose his transgressive aesthetics. The best way to do that was to mine his aphorisms, which really build on that way in which he used language to queer an idea. It takes you down one path and then goes the other way: "when you are alone with him, does he take off his face to reveal his mask?" Which is the opposite...most people would think does he take off his mask to reveal his true self. I was very frustrated because I couldn't find any critical analysis of Oscar Wilde's aesthetics and writings at the time. Finally Jonathan Dollimore's book came out, Sexual Dissidence: Augustine to Wilde, Freud to Foucault and that really was the piece that opened it up to me. By it's very nature the projects, especially my Film for Music for Film series is about translation to begin with. Another form of translation happened when I was grappling with the question of how to represent the dandy one hundred years later. There is a certain embodiment of that in Agnes de Garron, the founder of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, in the film, but I decided to embed the dandy in the emulsion of the film. That's where Wilde scholars always get frustrated with me when they come to see De Profundis. They are like where's Wilde? He's embedded in every frame of the film, he's infecting it.

LC: Why was this aspect of Wilde’s persona worth carrying forward? What made his dandyism transgressive?

LB: Wilde was from Ireland. He made it into the elite society of England, but he was really an invited guest. His mother was a feminist and he infiltrated these spaces, these gentlemen's clubs and would bring rent boys in and would dine them. He was shattering every class boundary and breaking every rule possible. And he was doing it in a very open way. I'm not so sure he was doing it to just be defiant, but he was not going to be muzzled or trapped. Some of it came with the celebrity aspect that he had achieved. It was his dandyism that attracted people. So I couldn't ignore the dandy aspect when making this film that dealt with Oscar Wilde, and there are different ways in which I decided to try and translate some of that. For example, in the first part - it’s in three sections and an intro story - it gets structurally established by the 32 minute center musical piece with the 16-minutes on each end, and then the 1-minute story in the beginning to throw it out of balance. In that first section after the story is sixteen minutes of Oscar Wilde aphorisms that are made into these sonic loops. I brought Agnes in to the recording studio and had her deliver 19 of the aphorisms but I asked her to read them in 5 different vocal personas. We have the voice that is embodying a certain persona, so we are translating sonically as well as visually. There are layers of translating both theoretical ideas as well as representations. The Radical Fairies represent a certain aspect of carrying on that tradition of the dandy and the translation of that. Affecting such a radical change on the image itself and really working on the materiality of the film and the skin of the film to alter the original image was as important as doing the sound with Agnes. The last thing I wanted to do was just have a voice over reading the aphorisms. I wanted it to be this wall of sound that emerged and disappeared, just like the images. You know that's a complicated thing to do with language and I credit Douglas Cohen who has such a brilliant approach to using the voice as a compositional tool.

LC: You said you wanted the readings of these aphorisms to be in five different vocal registers. Was this something you worked on with her, did you come to her with the five personas you wanted her to inhabit?

LB: We did that in the studio. It was a strategy on my part that I didn't know exactly what we were going to do with these aphorisms, but I knew at least that I wanted to have a variety of voices, having this multiplicity of voices coming out of one person. Agnes is a person of many personas anyway. There were things I knew Agnes could understand and pull off, like the stage-whisper, the sissy-boy, etc. There are many things in the creative process where you go with something, the idea was just to have complexity there and the composer was with me in the recording studio. We rehearsed with Agnes and we did it and re-did takes and all that. Then Douglas and I started to strategize and talk and we thought that there was such a rich palette and wondered what would happen if we stacked them and created these sound loops using all five voices. That's how it all began, and he sort of did his magic, but he had free reign. He was giving me a musical score in a sense, creating yet another part in the film from music, sound.

LC: You said you wanted the readings of these aphorisms to be in five different vocal registers. Was this something you worked on with her, did you come to her with the five personas you wanted her to inhabit?

LB: We did that in the studio. It was a strategy on my part that I didn't know exactly what we were going to do with these aphorisms, but I knew at least that I wanted to have a variety of voices, having this multiplicity of voices coming out of one person. Agnes is a person of many personas anyway. There were things I knew Agnes could understand and pull off, like the stage-whisper, the sissy-boy, etc. There are many things in the creative process where you go with something, the idea was just to have complexity there and the composer was with me in the recording studio. We rehearsed with Agnes and we did it and re-did takes and all that. Then Douglas and I started to strategize and talk and we thought that there was such a rich palette and wondered what would happen if we stacked them and created these sound loops using all five voices. That's how it all began, and he sort of did his magic, but he had free reign. He was giving me a musical score in a sense, creating yet another part in the film from music, sound.

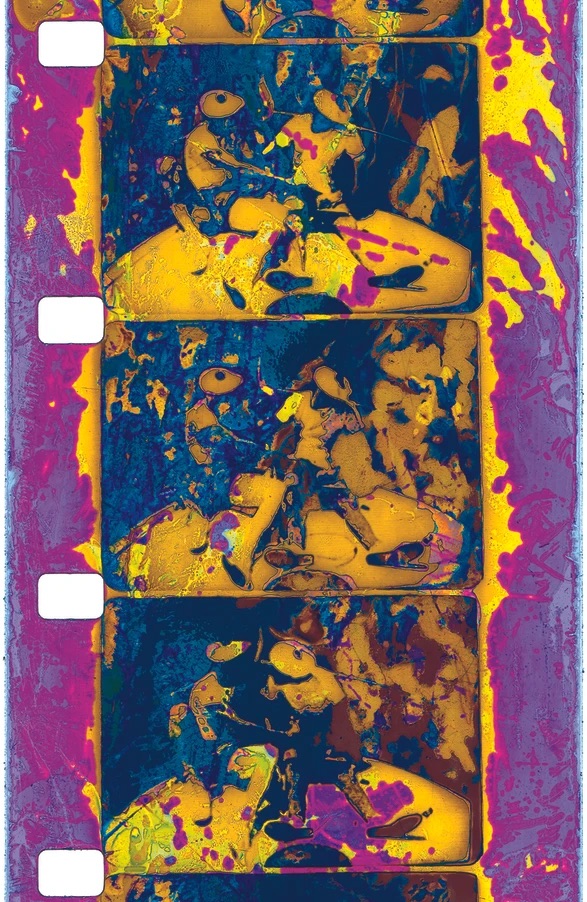

Lawrence Brose, Agnes de Garron, from the series De Profundis, 200. 16mm film stills printed on Epson Somerset Velvet Paper.

LC: So there’s a whole other level of translation happening here as well between text and sound and image, not just across these different media but between them as well.

LB: That is where we started with optical printing of found footage, combining of home movies, which I was very fortunate to get. That image on the wall is from the 1930s (points to a print on the wall of the CEPA loft). I was lucky to come across a trove of films - I used to go to estate sales and I would look for a projector, and as soon as I found a projector I found a box of films, and I just bought the films. This image was from a box of films that belonged to a doctor who, back in the 30s and 40s, had a 16mm film camera. Here in the US, I was working with a woman at a film festival on a whole big project which had to do with home movies. The interesting thing was in America it was always the male head of the household that did the filming of family events and you know parties, whatever - but in England, it's usually the female head of the household. That complicated getting images of adult males in home movies.

LC: Is that because the head of the household presumably has a heteronormative gaze and is not necessarily looking at men in that way that you would want to?

LB: With the exception, and this is what I found out with this box of films, when they are in a homosocial environment (camping trips, boating trips, different outings with men, military things) that behavior changes; and men are being imaged, and men are performing quite often for the camera. And for the gaze, the male gaze.

LC: Jane Ward recently published Not Gay: Sex between straight white men, in which she writes about the prevalence of sexual relations among white men. If you have been a gay man anywhere in the US in the last 40 years then you know there is this whole culture that happens below the frequency of normal hearing or normal vision. The doctor that has three kids and leads what appears to be a heteronormative life actually hooks up with men on the side. I wonder whether part of the research for De Profundis led to the discovery of evidence that would support this idea.

LB: To further tease that out, I used very early gay pornography and pushed it up against home movies to suggest a new reading of both. Very early gay erotica was made like home movies and circulated in a similar way, where gay men would gather and project gay erotica. I went as far back as the early Athletic Model Guild stuff and I thought Bob Mizer was interesting because he was pushing the envelope and always in court. He started adding art features like the large format two-frame print that was in the show of the muscle boys. There have been lots of readings of that piece during the show, the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the garden. In the frame, you will see there was a small little Greek column that would legitimize it as art. [laughter] So then you've got this splicing together. That was the other thing I was very aware of in this film: I wanted the viewer to feel the splice. Even though it feels very liquid, in some ways, there is this kind of jolting aspect to it, kind of like knocking against each other and knocking open doors of perception. But they are unified by the chemical process that joins them together.

LB: That is where we started with optical printing of found footage, combining of home movies, which I was very fortunate to get. That image on the wall is from the 1930s (points to a print on the wall of the CEPA loft). I was lucky to come across a trove of films - I used to go to estate sales and I would look for a projector, and as soon as I found a projector I found a box of films, and I just bought the films. This image was from a box of films that belonged to a doctor who, back in the 30s and 40s, had a 16mm film camera. Here in the US, I was working with a woman at a film festival on a whole big project which had to do with home movies. The interesting thing was in America it was always the male head of the household that did the filming of family events and you know parties, whatever - but in England, it's usually the female head of the household. That complicated getting images of adult males in home movies.

LC: Is that because the head of the household presumably has a heteronormative gaze and is not necessarily looking at men in that way that you would want to?

LB: With the exception, and this is what I found out with this box of films, when they are in a homosocial environment (camping trips, boating trips, different outings with men, military things) that behavior changes; and men are being imaged, and men are performing quite often for the camera. And for the gaze, the male gaze.

LC: Jane Ward recently published Not Gay: Sex between straight white men, in which she writes about the prevalence of sexual relations among white men. If you have been a gay man anywhere in the US in the last 40 years then you know there is this whole culture that happens below the frequency of normal hearing or normal vision. The doctor that has three kids and leads what appears to be a heteronormative life actually hooks up with men on the side. I wonder whether part of the research for De Profundis led to the discovery of evidence that would support this idea.

LB: To further tease that out, I used very early gay pornography and pushed it up against home movies to suggest a new reading of both. Very early gay erotica was made like home movies and circulated in a similar way, where gay men would gather and project gay erotica. I went as far back as the early Athletic Model Guild stuff and I thought Bob Mizer was interesting because he was pushing the envelope and always in court. He started adding art features like the large format two-frame print that was in the show of the muscle boys. There have been lots of readings of that piece during the show, the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the garden. In the frame, you will see there was a small little Greek column that would legitimize it as art. [laughter] So then you've got this splicing together. That was the other thing I was very aware of in this film: I wanted the viewer to feel the splice. Even though it feels very liquid, in some ways, there is this kind of jolting aspect to it, kind of like knocking against each other and knocking open doors of perception. But they are unified by the chemical process that joins them together.

LC: Do you mean “chemical process” literally?

LB: This starts out as black and white film, which I reproduce on the optical printer using a high contrast black and white film, hand process it, often solarizing it and then I put it through 20 different steps of colorizing it by hand - bleaching and toning, bleaching and toning. Even that process, when I talk about it, when I get to near the last step - and I'm really controlling this - when I get to this last step, I need to consider what I want the dominant color to be. I throw the colorized film back into the developer and it goes back to black and white. Then all of the color is still there, but it's a latent image, a latent fact. Then I make my choice and I throw it into bleach and then throw it into what I want the dominant color to be and then it just explodes in color. Even within the process, this latent aspect really discovers that in part. It may not necessarily come off in the film, but it's all part of the process of interpretation, if you will.

LC: If I'm understanding your description of the process correctly, there is not only a chance element to this, but that in many ways, it sounds like what you are doing is exposing the color that was there, but couldn't be seen, or exposing something that was already apart of the natural image in it's raw form. So you describe it as exposing the latency, and I think of latency as just being about there's something there that's just like a seed or a germ and then something triggers it and explodes into a flower or a virus.

LB: We can look at that as my own interpretation and my own desire to make these connections. I'm connecting things - home movies, gay erotica - I don't know if I am uniting them with the splice, but uniting them with the color palate. They become less distinguishable from each other and more united, and there is a kind of contamination in this. Even in processing these images, I'm pissing on the film and using bodily fluids. It's interesting - this is sort of an aside, I hired a publicist for the film and we were arranging all these screenings, but he decided to advertise, or at least pitch to, all of the gay sex magazines that advertised clubs and underground sex parties and things like that. They always seem to have some sort of art fag review. The art fag would always seem to end the review of De Profundis saying, if it is the filmmaker's intention to make us feel as imprisoned as Oscar Wilde did, then he has succeeded, and dear viewers - drugs help. [laughter] It was very effective because a lot gay men who would not go near an experimental film ever - even if it was a gay experimental film - were coming in, and then at the end complaining that they couldn't see the cocks [laughter].

LC: Speaking of cocks, in the interview with Scott MacDonald, you made a very pithy critique of how the LGBTQ movement went from being this radical force in the '60s & '70s through the responses to the AIDS Crisis and ACT UP to this normative movement in tune with right wing politics. It has obviously reinscribed certain heteronormative values. I'm wondering if another way of looking at that is that there is a kind of utopianism that had been over-written by neo-liberal capitalism.

LB: This starts out as black and white film, which I reproduce on the optical printer using a high contrast black and white film, hand process it, often solarizing it and then I put it through 20 different steps of colorizing it by hand - bleaching and toning, bleaching and toning. Even that process, when I talk about it, when I get to near the last step - and I'm really controlling this - when I get to this last step, I need to consider what I want the dominant color to be. I throw the colorized film back into the developer and it goes back to black and white. Then all of the color is still there, but it's a latent image, a latent fact. Then I make my choice and I throw it into bleach and then throw it into what I want the dominant color to be and then it just explodes in color. Even within the process, this latent aspect really discovers that in part. It may not necessarily come off in the film, but it's all part of the process of interpretation, if you will.

LC: If I'm understanding your description of the process correctly, there is not only a chance element to this, but that in many ways, it sounds like what you are doing is exposing the color that was there, but couldn't be seen, or exposing something that was already apart of the natural image in it's raw form. So you describe it as exposing the latency, and I think of latency as just being about there's something there that's just like a seed or a germ and then something triggers it and explodes into a flower or a virus.

LB: We can look at that as my own interpretation and my own desire to make these connections. I'm connecting things - home movies, gay erotica - I don't know if I am uniting them with the splice, but uniting them with the color palate. They become less distinguishable from each other and more united, and there is a kind of contamination in this. Even in processing these images, I'm pissing on the film and using bodily fluids. It's interesting - this is sort of an aside, I hired a publicist for the film and we were arranging all these screenings, but he decided to advertise, or at least pitch to, all of the gay sex magazines that advertised clubs and underground sex parties and things like that. They always seem to have some sort of art fag review. The art fag would always seem to end the review of De Profundis saying, if it is the filmmaker's intention to make us feel as imprisoned as Oscar Wilde did, then he has succeeded, and dear viewers - drugs help. [laughter] It was very effective because a lot gay men who would not go near an experimental film ever - even if it was a gay experimental film - were coming in, and then at the end complaining that they couldn't see the cocks [laughter].

LC: Speaking of cocks, in the interview with Scott MacDonald, you made a very pithy critique of how the LGBTQ movement went from being this radical force in the '60s & '70s through the responses to the AIDS Crisis and ACT UP to this normative movement in tune with right wing politics. It has obviously reinscribed certain heteronormative values. I'm wondering if another way of looking at that is that there is a kind of utopianism that had been over-written by neo-liberal capitalism.

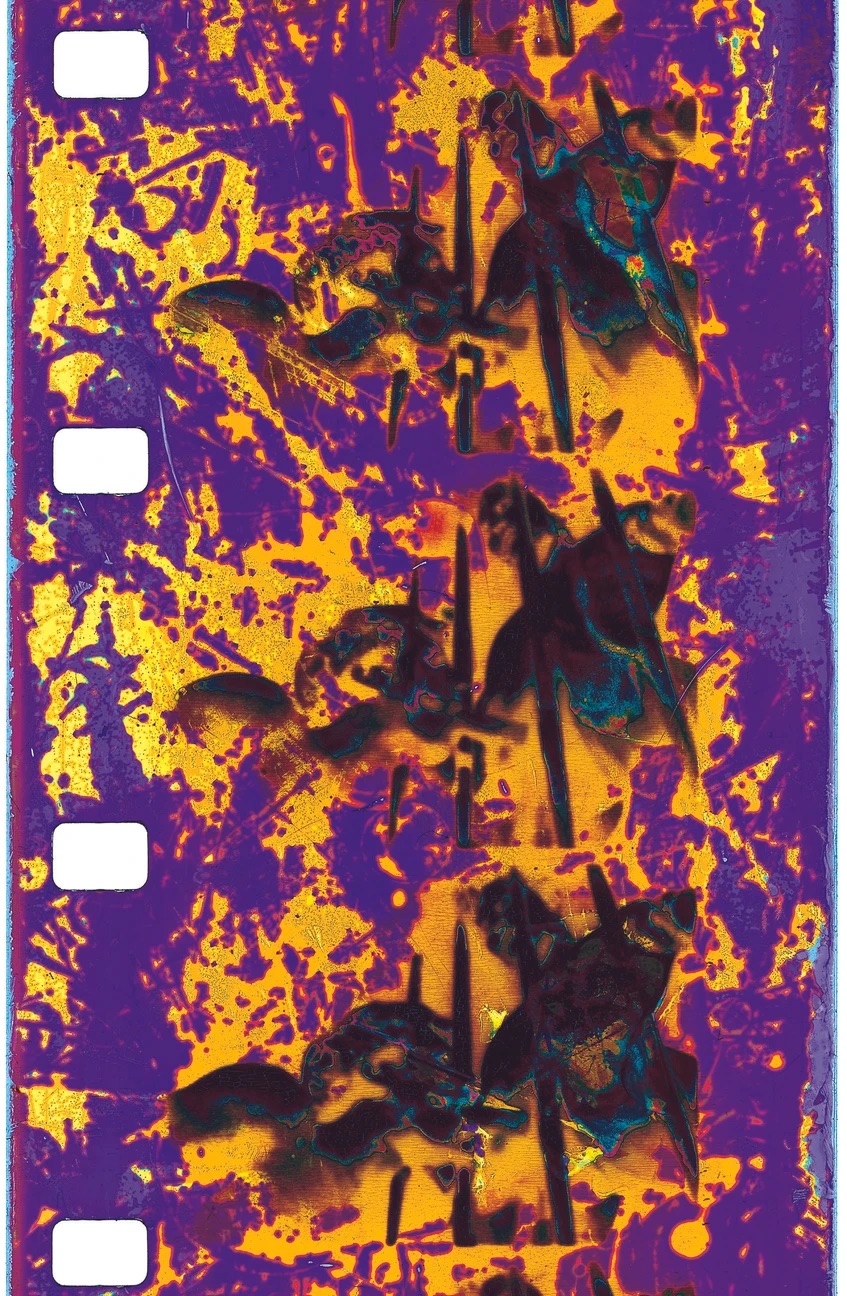

Lawrence Brose, Sailors Playing, from the series De Profundis, 2009; 16mm film stills printed on Epson Somerset Velvet Paper.

LB: I was arguing that at the time of making this film and De Profundis is a response on some level to the whole gay marriage movement. That was my politics at the time, that we are giving up so much, and it was being driven by white privileged males within the gay community who had everything except they had this one flaw, and that was disenfranchising to them. I felt that that was preventing the movement or the community from going for broke, to say no, we need to be inclusive here, we need to fight for different ways in which families are formed, and how do we protect all of us - using our outsider-ness to gain something. That is a fairly utopian positon, and I am impressed at how quickly things have changed with the legalization of gay marriage and how rapidly that actually took root and the success of that, which is starting to lead to opening other doors now. I still believe in what I believe in, but I'm impressed with what has been accomplished within this.

LC: I think of the histories of utopia and consumption as being deeply intertwined with one another. In the 19th century, French utopian socialists like Charles Fourier begin their thinking about utopia while they are deeply embedded in a new industrial, urban society that is at once deeply exploitative and promising of new social relationships. Fourier worked in the textile industry and encountered in arcades much like the ones in which CEPA is housed, the architectural forms of a new kind of utopian community. He saw these long corridors in which goods and consumers engaged each other as the possibility for new social interactions or “passional attractions” in the Phalanstère. So many of the communal societies that emerged out of Fourier’s thinking in the United States espoused a kind of “free love” in which nobody had ownership over the other. Yet, these concepts have historically been abandoned as failures and reprocessed back into capitlalism, so that the idea of the corridor of passional attraction becomes the shopping mall, or hooking up on Grindr.

LB: Which is a similar thing [laughter].

LC: Yes. But I’m suggesting that there was another kind of radical possibility in cities like New York in the 70s or 80s before AIDS in which sex was not so closely identified with shopping. Not only was there lots of sex but there were all kinds of social units outside of the heteronormative nuclear family. Somehow that energy got reformatted into gay marriage.

LB: I think what blunted a lot of that does go back to the AIDS crisis, then suddenly the horrific enters the arena and you know what happened. To live through that and then the utopian dream starts to dissipate for a certain kind of security.

LC: I think of De Profundis as operating as a utopian narrative, splicing together queer desire with queer politics and revealing new images of what that might look like through the chemical processes you’ve described. Bloch famously quotes Oscar Wilde in his conversation with Adorno on utopia: “A map of the world that does not include utopia is not even worth glancing at.”

LC: I think of the histories of utopia and consumption as being deeply intertwined with one another. In the 19th century, French utopian socialists like Charles Fourier begin their thinking about utopia while they are deeply embedded in a new industrial, urban society that is at once deeply exploitative and promising of new social relationships. Fourier worked in the textile industry and encountered in arcades much like the ones in which CEPA is housed, the architectural forms of a new kind of utopian community. He saw these long corridors in which goods and consumers engaged each other as the possibility for new social interactions or “passional attractions” in the Phalanstère. So many of the communal societies that emerged out of Fourier’s thinking in the United States espoused a kind of “free love” in which nobody had ownership over the other. Yet, these concepts have historically been abandoned as failures and reprocessed back into capitlalism, so that the idea of the corridor of passional attraction becomes the shopping mall, or hooking up on Grindr.

LB: Which is a similar thing [laughter].

LC: Yes. But I’m suggesting that there was another kind of radical possibility in cities like New York in the 70s or 80s before AIDS in which sex was not so closely identified with shopping. Not only was there lots of sex but there were all kinds of social units outside of the heteronormative nuclear family. Somehow that energy got reformatted into gay marriage.

LB: I think what blunted a lot of that does go back to the AIDS crisis, then suddenly the horrific enters the arena and you know what happened. To live through that and then the utopian dream starts to dissipate for a certain kind of security.

LC: I think of De Profundis as operating as a utopian narrative, splicing together queer desire with queer politics and revealing new images of what that might look like through the chemical processes you’ve described. Bloch famously quotes Oscar Wilde in his conversation with Adorno on utopia: “A map of the world that does not include utopia is not even worth glancing at.”

LB: When I was making De Profundis, I struggled with that second section, the prison letter. Part of that struggle added to this friction between the romantic existentialism of the letter, the musical setting of it, and what images I was working with. I was really kind of using that as that friction I was feeling. While I was making it, it was the bane of my existence. When I was actually showing the film at Harvard and later at Hamilton College, I think I even said that now, because of everything I have been through, I identify more with part two and the romantic existentialism of the imprisoned Wilde because that's what I experienced for the last 6 years- the brutality of Homeland Security. It's so deep the way in which the government with unlimited power, the things they were doing to people around me, and threatening people. They knew what they were doing when they came after me for child pornography. I was director of CEPA gallery at the time. This man who was at the time vice president of the board was the head of a major public relations firm and he said, “If you had just murdered somebody, we could deal with this.” When you hear that, the sting of that... there is such stigma on you, there's nothing anyone can do. That's why the government was shocked that I was fighting back and getting this support. It is interesting how - I didn't say this, so it's not about me bragging or anything - but I said this to somebody, about how my perception of my work has changed because it's being filtered through this different experience. They said, well that's the sign of great art, it can have a life that evolves. It was nice to hear. There is truth to the complexity of the film and there's a similar complexity to life. There are many reasons that lead me to start making prints from frame enlargements of the film. One is that when I'm editing the film, I'm doing everything by hand. I'm old school, tape-splicing, filling the whole studio space with strips and having them frame counted so I have exact timings. Color, they are all arranged by color palates and everything else, so I'm editing in that kind of way. But I'm looking at the entire frame. Sprocket holes, that whole area, the entire film is the image frame for me. And yet, when it gets projected you just get the center of the frame, and you lose all that other information. I wanted to be able to stop this 24 frames per second and just arrest them in a way, so the viewer has an ability to dictate their own engagement with it and can study it. With film, it's just going by. Often with films, like De Profundis, most people get to see it once. I've been lucky enough that it has had a good shelf life and a lot of people have seen it a number of times. Most people say that the third time is the charm because there are so many layers of meaning that the first time you are getting hit visually, orally, just everything, it's almost like washing over you. And after you get past that and get to the next viewing, things start to emerge: color connections to the words and different connections between the images and then there are more and more layers. There is one section of the film where almost the last part of the film, the section with the aphorisms and the men on the boat doing the oil rub, which keeps coming back in different variations. I get the image to one point where all the color and the actual images of each person on the boat is completely blown out, completely negative space, no image, just the outline of the form, and the aphorism is 'I saw then at once that what is said of a man is nothing, the important thing is who says it.' Wilde was referring to himself hearing about all the stuff said about him in court, thinking wouldn't it be fabulous if I was saying all this about myself. So it really goes into meaning and identity,which you aren't going to get the first time though because it's just so visually intense.

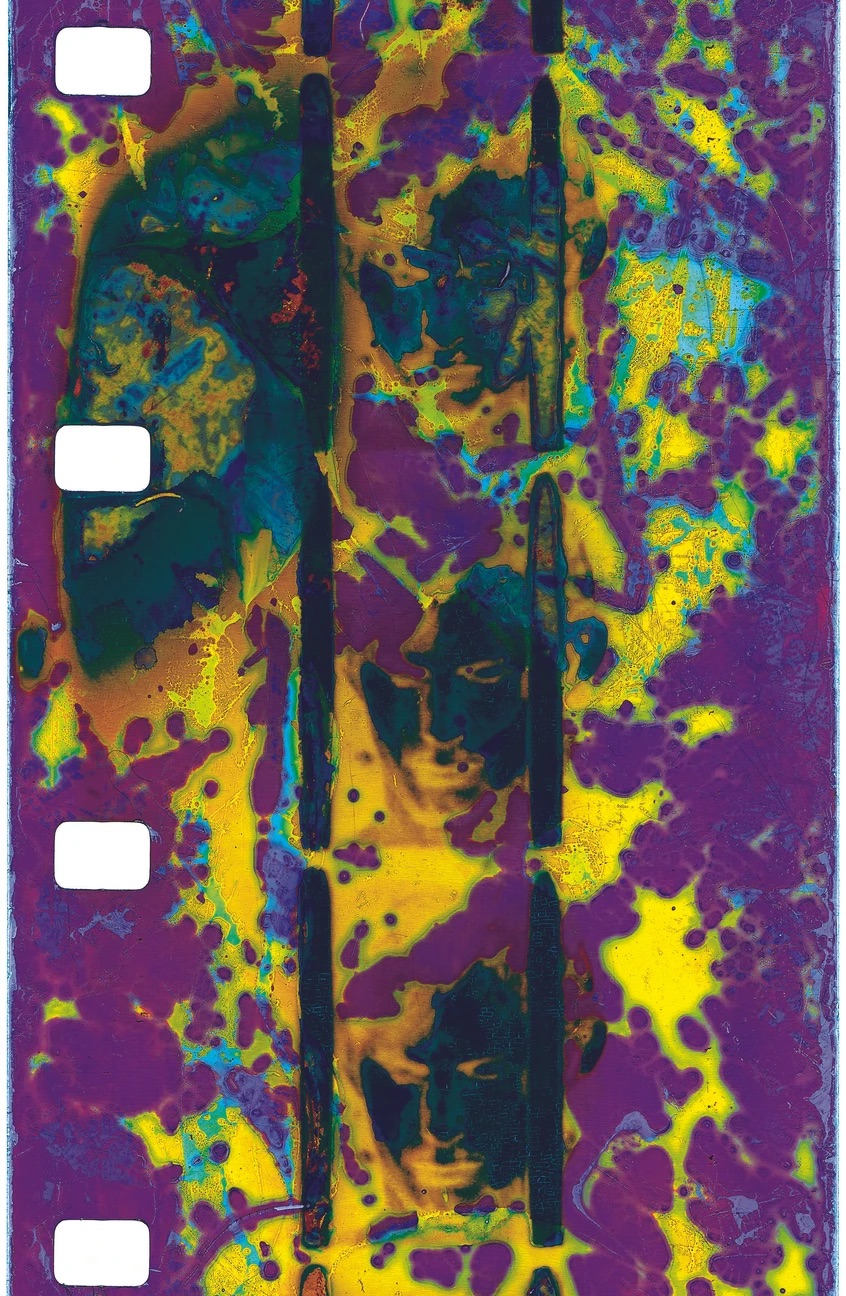

L: Lawrence Brose, BJ Bars, A Night at the Baths, Dungeon, from the series De Profundis, 2009; 16mm film stills printed on Epson Somerset Velvet Paper.

R: Lawrence Brose, Boy Bars #3, from the series De Profundis, 2009; 16mm film stills printed on Epson Somerset Velvet Paper.

LC: It makes me think also of how the audience, or how a viewer, appropriates a still image in a way that is different from a moving image. For me, it returns to Walter Benjamin’s observation that one appropriates architecture and film in a state of distraction. It doesn’t require the same intentionality or attention that one uses to look at a painting or read a text.

LB: The viewer is controlling the time in a still image. You as a viewer are engaging that image in a way that is of your own choosing in terms of proximity. If you watch people in a gallery, they will go back, then go forward. They look, they inspect, they go back, or they just walk by if they don't like it. There's a choice being made, and I like that as a completely different experience. That's why up until the show at BT & C Gallery, I had been showing the prints from the first part of the film - the very colorful hand processed imagery – at the Albright-Knox, but I created an extracted part 1 of the film with the aphorisms and put it onto a loop and put speakers throughout the gallery, so you'd have this audio experience with these still images. You'd also be able to see the images re-animated. But then I had this residency at the Institute for Electronic Arts at SUNY, Alfred. I already had the date for the show so we were originally just going to show all the earlier pieces, but when I got to Alfred, I thought, wait a minute, I've got to address the last six years of the case against me and it's here, it’s in the center section of De Profundis. I just have to pull out what would work as a still image. I really worked hard on that, and then I thought, no I've got to move forward because I got stopped from making the film I’m currently working on, titled Crossing the Line, because the government made me extract all of the homoerotic imagery from my loft, my home - books, academic books, everything had to go offsite and be secured. I was kind of stuck, plus mentally stuck, so I said I had to move forward and that's when I created the beginning of a new series of these photogravures from the Crossing the Line images which are altered in a different kind of way. So the show kind of backed out from the newest or the future moving forward, addressing my own incarceration in the center section of the De Profundis film, and then a few earlier works. So we decided to forget the sound and reanimating everything and create a quiet space, and I'm glad I did that. Just the opportunities all aligned, but I did find the altered image in the center section altered in a different way. It's translating my own experience of this psychic violence that I lived through for 6 years was there within the film because I was kind of addressing it by having to deal with Oscar Wilde's imprisonment, but it's the experience and the choices I make in selecting what images in the film to represent. its a long process of determining what makes an interesting image, but it may not translate into a print in a gallery. It might be interesting in movement on the screen, but now it's like a different choice when you arrest a moving image like that.

LC: It is as if you were moving from the black box of cinema to the white box of the gallery. The Albright-Knox was this intermediary space.

LB: The viewer is controlling the time in a still image. You as a viewer are engaging that image in a way that is of your own choosing in terms of proximity. If you watch people in a gallery, they will go back, then go forward. They look, they inspect, they go back, or they just walk by if they don't like it. There's a choice being made, and I like that as a completely different experience. That's why up until the show at BT & C Gallery, I had been showing the prints from the first part of the film - the very colorful hand processed imagery – at the Albright-Knox, but I created an extracted part 1 of the film with the aphorisms and put it onto a loop and put speakers throughout the gallery, so you'd have this audio experience with these still images. You'd also be able to see the images re-animated. But then I had this residency at the Institute for Electronic Arts at SUNY, Alfred. I already had the date for the show so we were originally just going to show all the earlier pieces, but when I got to Alfred, I thought, wait a minute, I've got to address the last six years of the case against me and it's here, it’s in the center section of De Profundis. I just have to pull out what would work as a still image. I really worked hard on that, and then I thought, no I've got to move forward because I got stopped from making the film I’m currently working on, titled Crossing the Line, because the government made me extract all of the homoerotic imagery from my loft, my home - books, academic books, everything had to go offsite and be secured. I was kind of stuck, plus mentally stuck, so I said I had to move forward and that's when I created the beginning of a new series of these photogravures from the Crossing the Line images which are altered in a different kind of way. So the show kind of backed out from the newest or the future moving forward, addressing my own incarceration in the center section of the De Profundis film, and then a few earlier works. So we decided to forget the sound and reanimating everything and create a quiet space, and I'm glad I did that. Just the opportunities all aligned, but I did find the altered image in the center section altered in a different way. It's translating my own experience of this psychic violence that I lived through for 6 years was there within the film because I was kind of addressing it by having to deal with Oscar Wilde's imprisonment, but it's the experience and the choices I make in selecting what images in the film to represent. its a long process of determining what makes an interesting image, but it may not translate into a print in a gallery. It might be interesting in movement on the screen, but now it's like a different choice when you arrest a moving image like that.

LC: It is as if you were moving from the black box of cinema to the white box of the gallery. The Albright-Knox was this intermediary space.

LB: I was still thinking as a filmmaker at the Albright-Knox, and thinking of this darkened space with just ten lights on the prints and then the time-based aspect of showing the prints and presenting the sound. It's hard to tell if it was insecurity or just still thinking as a filmmaker. I became more comfortable with the white space and part of that was from working with Anna Kaplan, the director and curator, and being able to talk through those kind of decisions. That has been a real luxury for me. I still came in with this idea that we could do sound and moving image, but the more we got to talking about it, I wanted to just let the work just speak.

LC: Where were you in the process when the case against you was first made?

LB: De Profundis was done in 1997 and then the print project began in about 2000, during my first residency of Institute for Electronic Arts. While I was touring De Profundis I was also shooting another film titled Crossing The Line, which was investigating the erotic politics of naval hazing rituals. I was also running CEPA gallery, which takes a lot, you can't be asleep at the wheel. Then this case began in 2008 when the agent came here, into the loft. It all happened because I was still playing for the internet. Even though CEPA was using the loft and was paying for the rest of the utilities, I was subsidizing the organization by paying for the internet.

LC: So you had moved out of here essentially?

LB: By that time, yeah. It was an open studio so all CEPA artists were coming in here and working, and using the Internet, which was not password protected. And apparently, theoretically, someone downloaded some child pornography, but because it was in my name, they came after me. They told me they targeted me because of De Profundis and, in fact, 100 of the images from the film, the film frames, the exhibition frames, were in the indictment as child pornography.

LC: This was the same office that persecuted Steve Kurtz (a founding member of the Critical Art Ensemble and professor of art at SUNY, Buffalo who was charged with bioterrorism in 2004), right?

LB: Well, Steve Kurtz, even though it fell under Homeland Security, I think it was the FBI, but it was still the same deal. The DA didn't target me, it was Homeland Security and ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement). They are the ones who said, we targeted you. That's in an affidavit, and they repeated it in front of my partner at home in the evening. 'We targeted you because of who you are in the community, because you are a filmmaker, because of your film De Profundis.’ I remember that because they mispronounced it and I had to keep correcting them. [laughter] They started rattling off the titles of the prints. The titles of the prints were meant to be provocative, but also to evoke back to Oscar Wilde and his imprisonment and his involvement with the rent boys, which is a term still used today in England. So Two Boys Fucking. You put that through the lens of child pornography...

LC: And boys takes on this whole other resonance...

LC: Where were you in the process when the case against you was first made?

LB: De Profundis was done in 1997 and then the print project began in about 2000, during my first residency of Institute for Electronic Arts. While I was touring De Profundis I was also shooting another film titled Crossing The Line, which was investigating the erotic politics of naval hazing rituals. I was also running CEPA gallery, which takes a lot, you can't be asleep at the wheel. Then this case began in 2008 when the agent came here, into the loft. It all happened because I was still playing for the internet. Even though CEPA was using the loft and was paying for the rest of the utilities, I was subsidizing the organization by paying for the internet.

LC: So you had moved out of here essentially?

LB: By that time, yeah. It was an open studio so all CEPA artists were coming in here and working, and using the Internet, which was not password protected. And apparently, theoretically, someone downloaded some child pornography, but because it was in my name, they came after me. They told me they targeted me because of De Profundis and, in fact, 100 of the images from the film, the film frames, the exhibition frames, were in the indictment as child pornography.

LC: This was the same office that persecuted Steve Kurtz (a founding member of the Critical Art Ensemble and professor of art at SUNY, Buffalo who was charged with bioterrorism in 2004), right?

LB: Well, Steve Kurtz, even though it fell under Homeland Security, I think it was the FBI, but it was still the same deal. The DA didn't target me, it was Homeland Security and ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement). They are the ones who said, we targeted you. That's in an affidavit, and they repeated it in front of my partner at home in the evening. 'We targeted you because of who you are in the community, because you are a filmmaker, because of your film De Profundis.’ I remember that because they mispronounced it and I had to keep correcting them. [laughter] They started rattling off the titles of the prints. The titles of the prints were meant to be provocative, but also to evoke back to Oscar Wilde and his imprisonment and his involvement with the rent boys, which is a term still used today in England. So Two Boys Fucking. You put that through the lens of child pornography...

LC: And boys takes on this whole other resonance...

Installation view, Albright Knox Art Gallery. Courtesy of Lawrence Brose.

LB: Yeah, oh yeah. I was silenced from talking about that. That was the most frustrating thing because we had the best forensic expert of her kind for this kind of case in the country saying, 'what the fuck did you do to the government? Because there is nothing here, it's bullshit.' Cases like this always plead out to the highest charge and they didn't expect me to fight. I was very fortunate to have people rally around me. It was a tough slough in the beginning. Like when the Steve Kurtz case happened, the Warhol foundation stepped right up and gave him $100,000. Jonathan Katz came to me with a proposal and we had 60 people that co-signed the application to support me to the Warhol Foundation. The Warhol Foundation said no. It was because of the stigma of the charges. On the other hand, people rallied around and we created the defense fund and lots of testimonials. So that's the relationship to the case to De Profundis. The exhibition prints were in the indictment and remained in the charges. But the film was finished. I'm wrestling now with getting back to the film, Crossing the Line and having an exhibition where I'm just mining what I already have. It would allow me to be less worried about creating a whole structural film and being back in the darkroom, almost needing the communal space of a residency. With the Institute for Electronic Arts, they don't just give you a workspace and leave you in solitude. Instead you have technical people all around you and you are able to operate as an artist and they are able to worry about all the technical stuff and 'let's scan this in and let's see what happens when we print this.' There was a woman from China who was an expert in photogravure printing, so we did that together and I had never printed like that. I'm finding that kind of experience necessary to bring me back into the art-making practice.

LC: So, you’re not finished with Crossing the Line, then?

LB: I've shot everything, now I just needs to go into the dark room and start doing all of the alchemy and all of that. I had envisioned, as a structure, and I used to have world maps of trade routes, as Crossing the Line is about the ritual of crossing the equator for the first time. So I want to look at maritime patterns and in these maps everything was between longitudinal and latitudinal lines; this grid set up and if you get a certain map which is a flat picture of the earth then those squares have different time limits and I wanted to assign, or come up with a formula to mapping out these various trade routes where they were crossing the equator and using that to inform how long each section before. I've never articulated that to anyone before.

LC: So, you’re not finished with Crossing the Line, then?

LB: I've shot everything, now I just needs to go into the dark room and start doing all of the alchemy and all of that. I had envisioned, as a structure, and I used to have world maps of trade routes, as Crossing the Line is about the ritual of crossing the equator for the first time. So I want to look at maritime patterns and in these maps everything was between longitudinal and latitudinal lines; this grid set up and if you get a certain map which is a flat picture of the earth then those squares have different time limits and I wanted to assign, or come up with a formula to mapping out these various trade routes where they were crossing the equator and using that to inform how long each section before. I've never articulated that to anyone before.

LC: It's so interesting listening to you speak about it because there are at least three temporal layers to what you are talking about. There's this natural time of the ocean and currents, and then there's this historical time of mercantile capitalism that can be read across these trade routes, and then there is this intimate personal time of those sailors on those ships, carrying those things across those trade routes and once they cross the equator, you have these intersection of these three temporalities.

LB: And the carnivalesque nature of it, and the usurping of authority, turning on it's head, and the whole bonding that goes on through these rituals. I've got all of these interviews with sailors who have done the crossing of the line - in fact, I just interviewed another sailor during my show. A book I was reading while thinking about this and the making of Crossing The Line, it's called Bligh's Bad Language, and it's about Captain Bligh and his misunderstanding of authority. He actually banned crossing the line on the HMS Bounty. This author was theorizing that his misunderstanding of the bonding aspect of that ritual led to the mutiny.

LC: How far away are you from finishing the film?

LB: I think that's a question for my psychiatrist. [laughter]

LC: Some of these questions have been a little therapeutic.

LB: You know, I really am still suffering post-traumatic stress. I went into this experience with the government, suffering from post-traumatic stress from my brother's suicide, which happened just prior to that. There was a lot going on, and now there is a lot to overcome in order for me to get to that place. I am working with the still images and mining those with the photogravure process, saying, ‘look, I'm not ready to go into the dark room and do all of that.' Because the optical printer is a machine for a mad person. [laughter] It's a crazy machine, but I feel comfortable enough just revisiting all this material that I have shot and collected. I've got actual images of crossing the line ritual, which was taken on a US battleship before it was banned. Then I had it cleaned up and transferred to film. I don't have an answer to that question. It will come. Also, in the middle of all this stuff with the government, the lab that I had my films with went out of business and threw out all my negatives. Now I'm in the process of trying to raise funds to digitize all of my films, because I have a print of each one. The first film is my AIDS film - I don't even have a video of it anymore, so it has to get done. In fact, I'm sending it off on Monday, but now I have to raise another $20,000, and of course this case broke me. I'm bankrupt, everything is gone, so I don't have any money.

LB: And the carnivalesque nature of it, and the usurping of authority, turning on it's head, and the whole bonding that goes on through these rituals. I've got all of these interviews with sailors who have done the crossing of the line - in fact, I just interviewed another sailor during my show. A book I was reading while thinking about this and the making of Crossing The Line, it's called Bligh's Bad Language, and it's about Captain Bligh and his misunderstanding of authority. He actually banned crossing the line on the HMS Bounty. This author was theorizing that his misunderstanding of the bonding aspect of that ritual led to the mutiny.

LC: How far away are you from finishing the film?

LB: I think that's a question for my psychiatrist. [laughter]

LC: Some of these questions have been a little therapeutic.

LB: You know, I really am still suffering post-traumatic stress. I went into this experience with the government, suffering from post-traumatic stress from my brother's suicide, which happened just prior to that. There was a lot going on, and now there is a lot to overcome in order for me to get to that place. I am working with the still images and mining those with the photogravure process, saying, ‘look, I'm not ready to go into the dark room and do all of that.' Because the optical printer is a machine for a mad person. [laughter] It's a crazy machine, but I feel comfortable enough just revisiting all this material that I have shot and collected. I've got actual images of crossing the line ritual, which was taken on a US battleship before it was banned. Then I had it cleaned up and transferred to film. I don't have an answer to that question. It will come. Also, in the middle of all this stuff with the government, the lab that I had my films with went out of business and threw out all my negatives. Now I'm in the process of trying to raise funds to digitize all of my films, because I have a print of each one. The first film is my AIDS film - I don't even have a video of it anymore, so it has to get done. In fact, I'm sending it off on Monday, but now I have to raise another $20,000, and of course this case broke me. I'm bankrupt, everything is gone, so I don't have any money.

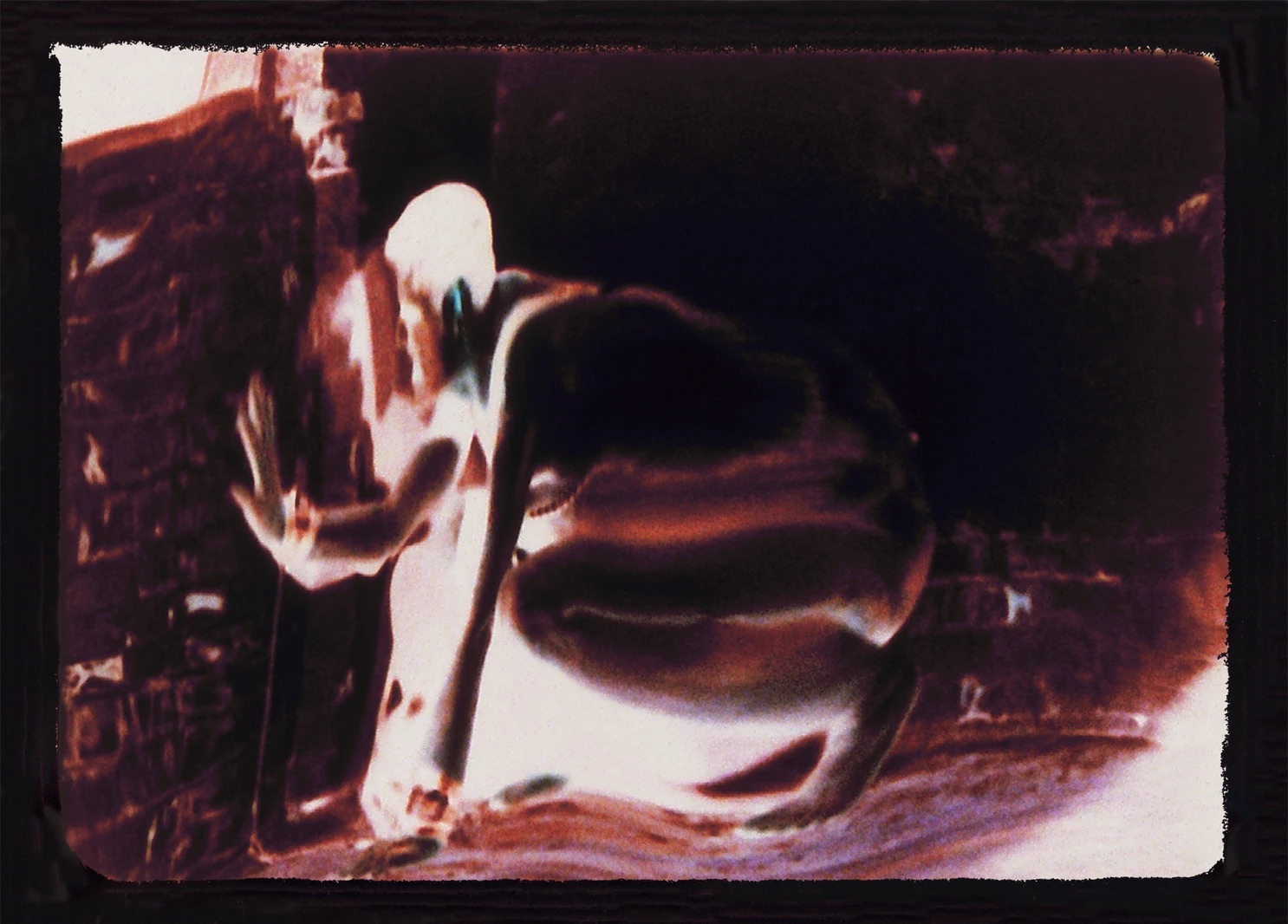

L: Lawrence Brose, Cabin Boy - Longing for First Mate, Photogravures, 2015, from the series Crossing the Line. Film stills printed on Hahnemuehle Museum Etching Paper.

R: Lawrence Brose, Jason - Shore Leave, Photogravures, 2015, from the series Crossing the Line. Film stills printed on Hahnemuehle Museum Etching Paper.

LC: My last question was related to that and how to institution building because this has also been a big part of your life. I mean, you founded this really influential not-for-profit arts space here in Buffalo. How does that intersect with your creative life, like why bother?

LB: I certainly was at a high point in building CEPA. I didn't start CEPA, we had other directors: Bob Hirsch, Gail Nicholson, Biff Henrich. I was handed it and was artistic director for 10 years and director of public art, and when Bob Hirsch decided to leave he left it as a healthy organization. I was able to take it into the stratosphere and really build it. Now it's interesting, I'm teaching at the University in the Department of Art and Photography, and I'm running a speaker series. I'm doing some consulting for other not-for-profits. I felt everything I did was art, even building that organization and curating shows, that's an art practice in and of itself. Finding money is an art practice. To create a healthy organization where you can commission artists to create new work, what better thing to be doing, except for making your own artwork, I suppose. Now that this is over, there is more attention to my work - unfortunately, because of this. I wouldn't wish this on anyone, to have to go through just to make a career in the arts. [laughter] I lost everything I own, but I own my artwork, my art practice. But that's something that cannot be taken from me.

LC: It strikes me also, listening to you talk, this past hour and a half or so that one of the things you are doing, that you have been doing, it not just institution building, but community building as well. That seems consistent with your own intellectual interests and understanding those queer forms of community that are not based on the heteronormative nuclear family.

LB: I certainly was at a high point in building CEPA. I didn't start CEPA, we had other directors: Bob Hirsch, Gail Nicholson, Biff Henrich. I was handed it and was artistic director for 10 years and director of public art, and when Bob Hirsch decided to leave he left it as a healthy organization. I was able to take it into the stratosphere and really build it. Now it's interesting, I'm teaching at the University in the Department of Art and Photography, and I'm running a speaker series. I'm doing some consulting for other not-for-profits. I felt everything I did was art, even building that organization and curating shows, that's an art practice in and of itself. Finding money is an art practice. To create a healthy organization where you can commission artists to create new work, what better thing to be doing, except for making your own artwork, I suppose. Now that this is over, there is more attention to my work - unfortunately, because of this. I wouldn't wish this on anyone, to have to go through just to make a career in the arts. [laughter] I lost everything I own, but I own my artwork, my art practice. But that's something that cannot be taken from me.

LC: It strikes me also, listening to you talk, this past hour and a half or so that one of the things you are doing, that you have been doing, it not just institution building, but community building as well. That seems consistent with your own intellectual interests and understanding those queer forms of community that are not based on the heteronormative nuclear family.

LB: I remember one of the first people that came to my aid outside of my immediate community here was Sarah Schulman. She jumped right on and she's friends with Judith Levine and Debby Nathan. And they are one of the founders of the National Center for Reason and Justice, who sponsor people and therefore, set up a not-for-profit fund for a person unjustly accused. They fast-tracked my case - usually it takes 6 months to a year to set up a fund, but with Sarah doing this they set it up immediately. I said, Sarah, I can't thank you enough but why?. Her response was this is why we call it a community. It's interesting for me to look back on what I was doing at CEPA as this idea of community, and I think that's why I had so many people rallying around me. The letters to the judge - usually, they get about 10 or 20 letters asking for leniency. I had to cut it off at 120. Even Paul Cambria, the lead attorney said we have never had this many letter for a client. So I could have gotten more, from all over. That was a humbling experience, and reading those letters... Once again silver lining, by going through this experience, rallying around me and asking for support, that is a thing people only get at their own funerals. I got to experience it in life. These were really heartfelt. I'm really humbled by that whole thing that it kind of came back to me. Once again, I didn't think about it as even community building, I was just doing this because it was part of my belief system of supporting artists and that is how I was able to raise money, because I believe so much in what I was doing. And that passion translates to other people.

More on Lawrence Brose here: @broselawrence

More on Lawrence Brose here: @broselawrence

Lawrence Brose, Floor Mylar, from In Carcere et Vinculis, 2015. Film still printed on Hahnemuehle Museum Etching Paper.